Notes from the stacks, vol. I

A plea for literature, intellectualism, and the return of the literary salon

“I don’t know what I think until I write it down.”

-Joan Didion

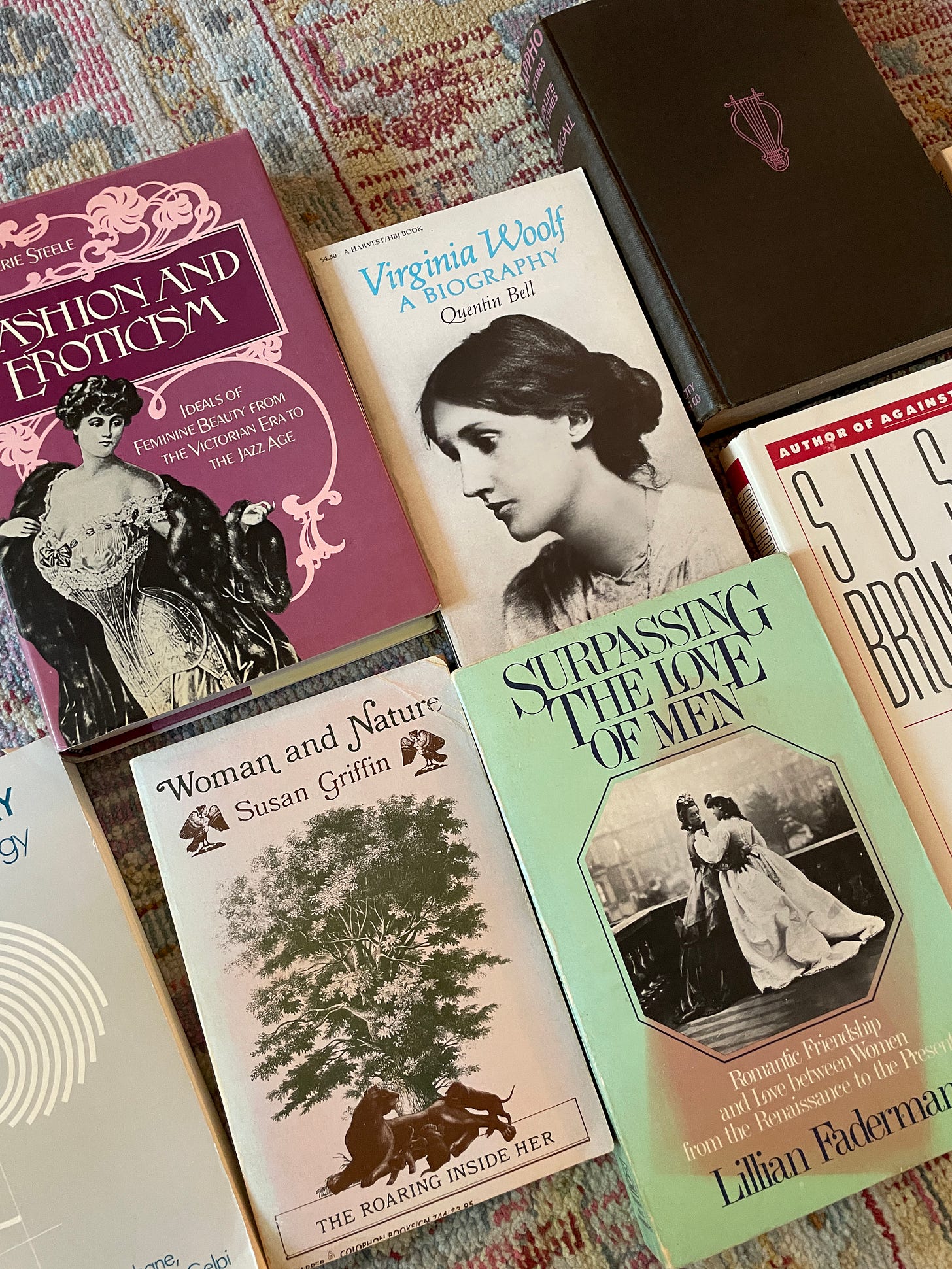

Yesterday at the bookstore, a friend dropped off three boxes full of vintage feminist texts ranging from as far back as the 1930s. A biography of Virginia Woolf, texts by Lillian Faderman – brilliant scholar of LGBTQ history – and a first edition of Sappho of Lesbos: Her Life and Times, among others. My partner and I dug carefully but eagerly through the boxes, pulling out each title like a treasure. There is something to be learned from these historic texts, a way of writing and of viewing the world that transports you back to a time when literature and intellectualism were valued as much as the artists who created these works. With the presence of AI on the ever-terrifying rise and society’s attention span dwindling by the millisecond, I feel a deep sense of urgency to preserve these texts and push them into the hands of everyone who enters the bookstore.

Anyone in the book world is well aware that books have begun to boom again over the last few years, and as a bookseller I am of course thrilled to see more people reading. The bookish sides of Instagram and TikTok (nicknamed “bookstagram” and “booktok” affectionately) have exploded, due in large part to the COVID-19 pandemic. People who hated reading as kids have developed a newfound love for it. Authors with self-published books have seen their careers skyrocket. And all of that is wonderful. But it snags at something deep within my soul to see books become nothing more than a trend, to see storytelling boiled down to a Canva graphic of tropes. Literature should make you think, should challenge you intellectually and expand your worldview, yet it feels as if reading has now become nothing more than quick entertainment.

We have become a culture of dopamine addicts, desperate for any instant gratification we can get our hands on. Bookstagram and booktok are filled with videos like “see how much I can read in a day” where someone finishes multiple hundred-page books in a week, or catchy colorful graphics like “short books to help you reach your reading goal.” The Goodreads Reading Challenge tasks readers with seeing how many books they can read in a year, with the focus being solely on quantity alone. It seems that in this digital age, the point of reading has shifted from gaining new ideas and perspectives to checking items off a list or gaining social media clout. Literature has been turned from an art form into a numbers game.

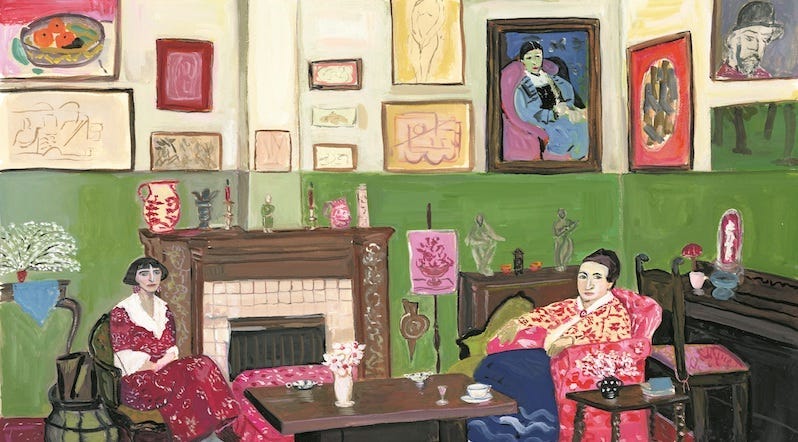

Literary salons began to boom in Paris during the 18th century. Hosted mainly by women, they were a place to exchange ideas, discuss literary criticism, and cultivate intellectual discourse. One of the most famous salons in 20th century Paris was that of writer Gertrude Stein and her partner Alice B. Toklas. Stein’s salon was frequented by writers like Ernest Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. American individualism has convinced us that reading and writing are solitary activities, when in reality they are activities that come alive when discussed amongst a group (and not in the comments section of an Instagram post). Words gain new life and meaning. Ideas shift and evolve. Perspectives broaden and horizons expand. Art and literature are not meant to be perceived within the silo of a smartphone.

It seems to me as if apathy and escapism have become our response to the horrific reality happening around us. From pandemics to genocide to the swift rise of fascism, most people would agree the world is a terrifying place to exist at the moment. And I understand that brings feelings of hopelessness, fear, and indecision. What I don’t understand, however, is using that as an excuse to turn off our brains and consume nothing of intellectual substance. Intellectualism is an active form of resistance. Giving in to automation and cheap entertainment — essentially giving in to brain rot — is playing right into the hands of the oppressors. When we don’t think critically and engage actively with the world around us, we become easier to silence and control.

The other day a customer came into the store and picked up a book from our new releases table. “Does this have any smut?” they asked me, eager. I told them that, no, it did not, and watched their expression falter. It was a novel I had read recently and enjoyed, so I tried to sell them on it, talking about how well written and thoroughly researched it was and how I loved the characters. The customer’s eyes glazed over while I spoke. “I think I’m going to pass,” they said.

I am not here to judge anyone’s reading habits. I am happy if anyone chooses to read at all instead of doom scrolling in their bedroom for hours. I am not here to say that any one genre or era of literature is more valid than another. All I am asking is for readers to consider the ways in which they engage with the words they consume, and to not consume just for consumption’s sake. As Virginia Woolf said in her short essay How Should One Read a Book?, “The only advice, indeed, that one can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions.” So I encourage you to think critically about what you read and why, what purpose it serves and what you stand to gain from it. Dig beneath the surface and explore the layers beneath. Here’s to reading, always a worthy endeavor.

Signing off from the stacks,

Catherine

Thanks for reading volume I of Notes From the Stacks, essays and reflections on all things literary from a writer and indie bookstore manager. Feel free to leave a comment about what you thought of this volume or what you want to see next. You can follow me on Instagram at @catherineinwords for more.